# 43114

[ORSMOND, John Muggridge, 1788-1856]

Autograph letter in the Tahitian language, written by a chief of Bora Bora to the LMS missionary, Rev. John Muggridge Orsmond. Bora Bora, 1822.

$45,000.00 AUD

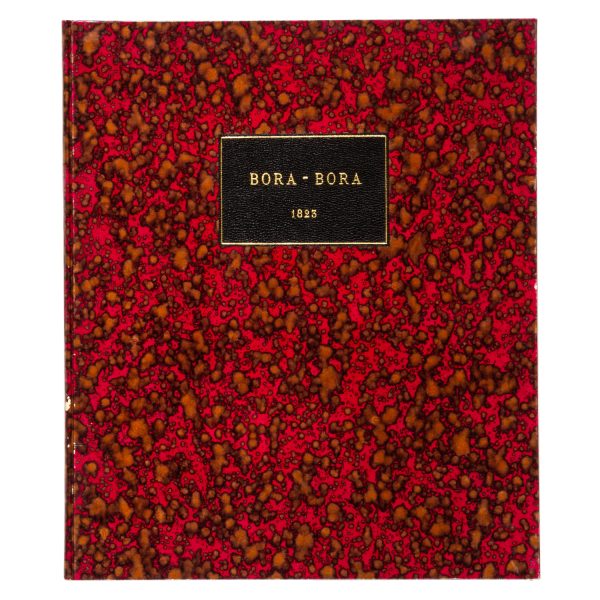

Manuscript in brown ink on laid paper, 3 pp. on quarto bifolium, 175 x 150 mm; letter in the Tahitian language addressed to missionary Rev. John Orsmond at Tahiti, written entirely in the hand of an unidentified chief of Bora Bora, signed ‘Porapora’ at the foot; undated, but probably 1822 (see below); traces of original folds, some marginal repairs to verso of last side, but well preserved; tipped onto archival paper, bound in modern marbled boards, along with a manuscript note dated 3 March 1826 written and signed by René Primevère Lesson, surgeon and naturalist on the Duperrey expedition, explaining that he is presenting the original letter (which had been given to him by Orsmond on Bora Bora) to Monsieur Berthevin, and stating that a French translation, together with a facsimile of the letter, have been published in the Journal des voyages (January 1826).

A remarkable letter which manifestly demonstrates how rapidly and profoundly the Christian faith was able to penetrate an Eastern Polynesian society through the agency of the LMS missionaries in the first decades of the nineteenth century.

Provenance:

Rev. John Muggridge Orsmond (1788-1856)

René Primevère Lesson, naturalist and surgeon (1794-1849)

B. Berthevin (ownership monogram stamp in blue)

Henri Ledoux private collection, Paris (ownership monogram stamp in red)

Libairie Clavreuil, Paris

TRANSLATION

Here is our English translation of Orsmond’s own French translation of the letter, published in Journal des voyages, number 87, January 1826. (Note that Orsmond could not render a suitable translation for three of the Tahitian words).

‘Dear friend, Mr Orsmond.

Greetings to you, in the true God and in Jesus Christ, the true King, through whom the power of hell has been destroyed: this is the word we address you; it is that of all of us, brothers and sisters, because of our love for you, which accompanies you in your journey on the deep sea, and in your visit to the missionaries who live in Tahiti and Moorea. This is the prayer that we address to God for you from the bottom of our hearts.

Since the gospel is no longer preached to us, we are like children who have no parents, like the bonito that cannot enjoy rest. We have the custom of participating in the sacrament [oma]; we must continue to do this. Our body alone is separated from you; our memory and love for you are not lost.

Every day is spent in prayer so that we persist in our conduct on this earth of ours, we cling to the gospel of Jesus, and we partially bear the evil; we are, like [otaha], struck by [atoa], exercising our patience with the evil customs that are on earth.

Na Terena, and all the brothers and sisters, and also friends Tyerman and Bennet [i.e. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, visiting LMS missionary inspectors], we greet in Jesus; we have love for you both; your image is not lost to us; it is within us, and will never be lost until our bodies are mixed with dust, until we are reunited in heaven.

Porapora.’

THE EVANGELISATION OF BORA BORA SOCIETY

In 1815, after victory over the traditionalist force in the battle of Fe’i Pi in Punaauia on the island of Tahiti, the Protestant party of Pomare II – who had converted to the Christian faith in 1812 – became supreme rulers of Tahiti. Pomare’s warriors introduced Christianity to the nearby Bora Bora group in 1816. In 1818, the inhabitants of Bora Bora made a request to the LMS missionaries of nearby Huahine (86 km away) and Moorea (230 km distant) for religious books and pastors for the islands. Consequently, Rev. John Orsmond visited Bora Bora for the first time that same year, and helped to organise the first church there. He returned to Bora Bora in 1820-21, and again in 1823.

The writer of the present letter expresses his sadness and regret at Orsmond’s long absence from Bora Bora, and his concern that his people may lapse back into the ‘evil customs’ of traditional society. Indeed, he probably had not seen Orsmond since 1821. The reference to Tyerman and Bennet is helpful in providing an approximate date for the letter, since the two missionaries arrived in Tahiti in September 1821, and departed for New Zealand May 1824; and, as we know that Orsmond visited Bora Bora for a third time in 1823 (his journal of missionary activity in Bora Bora during 1823 is held in SOAS, University of London), we can assume with a fair degree of certainty that the letter was written at some point in 1822.

ORSMOND AND THE NEW SOUTH WALES-TAHITI MISSIONARY CONNECTION

Rev. John Muggridge Orsmond (1788-1856), a nonconformist trained theologian, was ordained in Portsmouth in December 1815. Accompanied by his wife Mary, he arrived in Sydney, New South Wales in December 1816 aboard the Surry. He was one of a significant group of LMS missionaries to work in or pass through the colony in the Macquarie era. These men, among them L. E. Threlkeld, John Williams, William Ellis, Robert Bourne, David Darling, and George Platt, had been selected by the LMS to ‘infuse life into the Pacific mission stations’ following the declaration of peace in Europe in 1815 (Gunson, Neil. Australian reminiscences and papers of L. E. Threlkeld, missionary to the Aborigines 1825-1859. Australian Aboriginal Studies No. 40. Ethnohistory Series No. 2. Canberra : AIAS, 1974, p. v). During his brief time in Sydney, Orsmond was engaged in teaching Irish convicts to read and write; he also studied with the family of Dr. William Redfern. In February 1817 he departed Port Jackson for the Society Islands (Tahiti), whose indigenous population had undergone a nominal conversion in 1815. The Orsmonds arrived at Eimeo (Moorea) on 20 April 1817.

In January 1819 Mary died in childbirth, and her baby a few days later; as it was not considered desirable for missionaries to carry out their work in a single state, Orsmond spent several months in Sydney in 1819-20, where he married Isabella, daughter of Isaac Nelson, an emancipist farmer and the first schoolteacher at Liverpool, on Christmas Day 1819. Orsmond returned to Tahiti with Isabella, where he would spend the remainder of his life. Not content with serving as a missionary, however, he dedicated himself to the study and preservation of Polynesian language and culture. He was appointed principal of the South Sea Academy in Moorea, and his work as a Polynesian scholar and success as an educationist had some influence on John Dunmore Lang back in New South Wales.

In 1848 Orsmond presented an important manuscript on the history of Tahiti to French colonial official Charles François Lavaud, but it was lost before it could be published in Paris. Orsmond’s granddaughter, the Tahitian scholar Teuira Henry (1847-1915), was able to reconstruct much of the original manuscript using Orsmond’s notes: Ancient Tahiti was ultimately published in 1928 by the Bishop Museum. O’Reilly (Bibliographie de Tahiti et de la Polynésie française) notes that Orsmond was regarded by J. A. Moerenhout (1796-1879), US Consul to Tahiti, as ‘the most common European in Polynesian traditions’.

THE PUBLICATION HISTORY OF THE LETTER

The letter to Rev. Orsmond from a Bora Bora chief was presented personally by Orsmond to René Primevère Lesson, surgeon and naturalist on the Duperrey expedition, in June 1823, when the Coquille called at Bora Bora. It was Lesson who facilitated the publication of the letter in facsimile in the prestigious Parisian periodical Journal des voyages, number 87, January 1826. (We include photocopies of the relevant pages). The facsimile was accompanied by Orsmond’s own French translation, and a contextual essay titled Progrès de la civilisation à Taïti. To paraphrase some of the points made by the anonymous author of this essay:

Tahiti has been completely transformed since its discovery by Quiros in 1606; it is no longer the same as it was in the time of Wallis, Bougainville or Cook. Barbarous customs and gruesome practices such as human sacrifice have disappeared, now replaced by Protestantism – the only faith in the islands. Education has been introduced and many of the inhabitants can now read and write. Within a few years, Tahitians will dress entirely in the European manner; tattooing will no longer be seen, as it has already been outlawed by the missionaries. The Tahitian language has already been mastered, more or less: the missionaries work unceasingly on preparing a grammar and dictionary; a hagiography, an arithmetic primer, and a brief history of the islands have been printed on presses on Moorea and Tahiti. The Tahitian alphabet ‘has only 16 letters’ and its words are ‘composed almost entirely of vowels’. Their language might be considered very gentle, if it were not for the bad habit of shouting to make oneself heard. The language is reminiscent of that spoken on New Ireland. The natives have also adopted many European words into their language, for objects or concepts for which there is no Tahitian equivalent; examples of this phenomenon will be seen in the letter that is produced in facsimile. In this letter one will also find proof of the progress of civilisation in this part of the world and of the spread of human knowledge; this is absolutely remarkable when one considers that it is only 40 years since the first Tahitian (i.e. Ahutoru) was brought to Europe by Bougainville. There can be no doubt that the intelligence of this people is great and will soon place them in the ranks of other European colonies.

Soon after the letter’s publication in facsimile and translation, Lesson gave the original letter to a Monsieur Berthevin, in March 1826. (Lesson’s covering letter to Berthevin has been preserved in the same binding as the Bora Bora letter). Some twelve years later, Lesson included a French translation of the letter, along with his reminiscences of meeting Rev. Orsmond and his wife Isabella on Bora Bora in 1823, in his Voyage autour du Monde entrepris par ordre du Gouvernement sur la Corvette La Coquille (pp. 463-5).