# 45671

EMPRESS SHOTOKU-TENNO (718 - 770 CE)

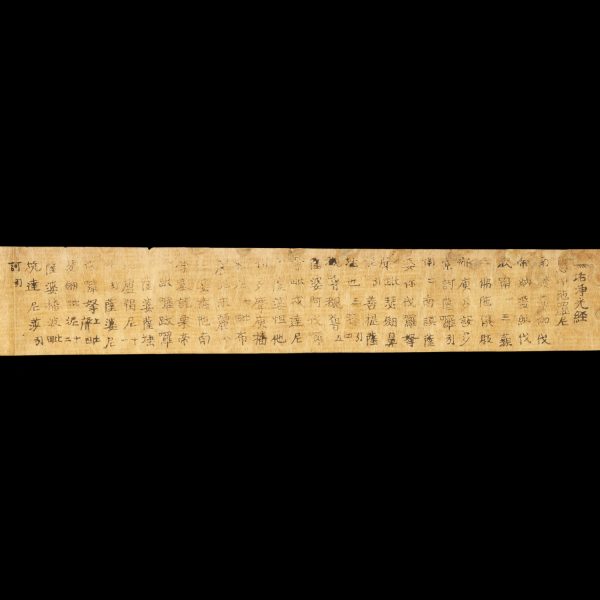

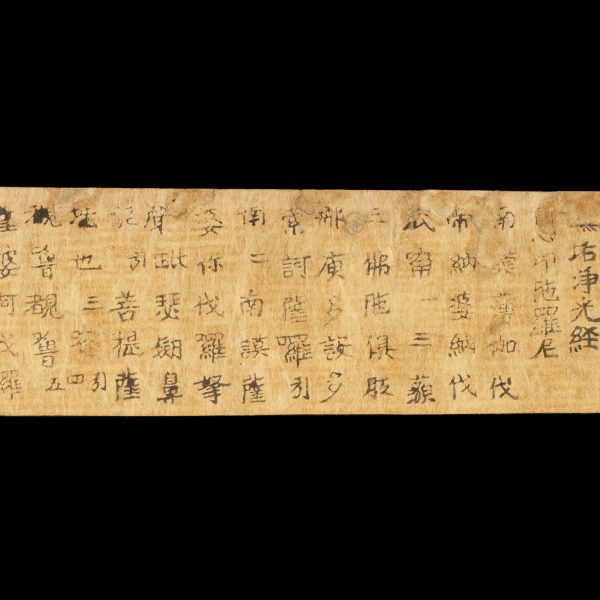

Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī (百万塔陀羅尼) : an example of the earliest reliably datable printed text

$85,000.00 AUD

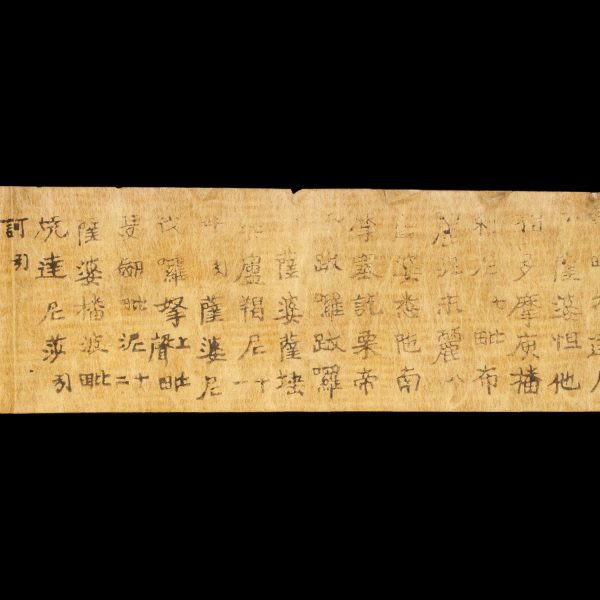

Japan : Nara period [764 – 770 CE]. Three-tier turned wooden pagoda made of hinoki (Japanese Cypress), with original white gesso wash, separate turned katsura wood finial (small edge chips to the rings), overall height 220 mm; the cavity of the pagoda containing the original printed dhāraṇī (55 x 458 mm) with 31 lines of text in 5 columns; insect damage with some loss to the outer margin, the dharani expertly conserved and laid down, stable and sound; a fine example presented with a fine Meiji era lacquered stand. Housed in a modern paulownia wooden tomobako storage box

A rare example of the earliest printed text to have survived in Eastern or Western cultures that can be verifiably dated, predating the movable type of Gutenberg by some seven centuries.

In the year 764 CE, the Empress Shōtoku (称徳天皇) commissioned one million (hyakuman) miniature wooden pagodas (tō) for distribution to ten major Buddhist temples in Japan. Known collectively as the Hyakumantō (百万塔), each contained a small scroll on rice paper with a Buddhist mantra or prayer (dhāraṇī), which was most likely printed on a bronze tablet – although some scholars suggest wooden blocks were used.

The Mahayana branch of Buddhism had reached China from India towards the end of the Han period, around 150 CE. It spread from China to Japan in the 6th century CE, where it quickly established itself as the primary form of Buddhism. In Mahayana devotional practice a dhāraṇī is a charm or prayer. Each of the Hyakumantō contained a dhāraṇī from the body of texts known in Sanskrit as the Vimalasuddhaprabhasa mahadharani sutra, and in Japanese as Mukujōkō daidarani kyō (無垢淨光大陀羅尼經). The six main sections of the sutra had been translated into Chinese by the Central Asian monk Mituoxian between 680 and 704 CE, and it became one of the key sutras of Empress Shōtoku’s period. Chinese was the principal language of worship, as there was no formal standardisation of written Japanese at this early date; consequently, the dhāraṇī contained in the Hyakumantō were printed in Chinese script. However, the prayers themselves – unlike the main text of the sutra – were not translated, as Carter notes:

‘The charms were merely transliterated, the Sanskrit sounds being represented as nearly as possible by Chinese characters. It is these Sanskrit charms in Chinese characters that were printed and rolled up and placed in the wooden pagodas.‘ (Carter, Thomas Francis, The invention of printing in China and its spread westward. New York : Columbia University Press, 1931, p. 37).

As well as being intended for the expiation of sin and the accumulation of religious merit, the prayers were believed to have apotropaic powers, which meant that each of these diminutive pagodas was in essence a protective talisman to ward off evil spirits. Each of the Hyakumantō contained one of the six prayers or charms taken from the original Sanskrit sutra (Carter, p. 36). The Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī were dedicated and distributed to the ten major temples in the Kansai region of Japan at the time: Sadai-ji, Daian-ji, Shitennô-ji Yakushi-ji, Tôdai-ji, Hôryu-ji, Sûfuku-ji, Kôfuku-ji, Genkô-ji, and Kôfuku-ji, where they were housed in specially constructed halls known as shōtōin.

The earliest record we have of the commission of the Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī is found in the Shoku Nihongi (続日本紀) of 797 CE, a 40-volume work of national history which documents their creation. Carter (ibid., p. 36) provides a translation of the relevant passage in the Shoku Nihongi:

‘In the fourth month of the year 770, after the eight years of civil war had been brought to an end, the empress made a vow and ordered the production of one million three-storey pagodas, four and a half inches high and three and a half inches in diameter at the base. Within these were to be placed the following dharani charms [here follow the names of the six charms]. When this work was finished, they were distributed among various temples.‘ (ibid., p. 36).

Although it is questionable whether one million of the Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī were actually made, it would appear certain that at least several hundreds of thousands were – an unprecedented example of mass production in Japan, which came at great personal expense to the empress. We are certain that a small army of artisans was responsible for their creation: from the evidence provided by a maker’s mark on many of the surviving examples, it has been ascertained that no fewer than 157 artisans were engaged in their production.

There are various theories as to why the Empress of Japan commissioned the Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī. The project commenced in 764 at the conclusion of the Fujiwara no Nakamaro Rebellion (藤原仲麻呂の乱), and continued until the Empress’ death in 770 CE. Her act is formally recorded as a gesture of thanks for the crushing of the rebellion; other sources speculate it was an act of penance stemming from her association with the monk Dōkyō. Quite possibly it was related to both events, but there can be little doubt that at least part of the impetus for it derived from the empress’ time spent as a nun in the years between her reigns (see below). Ultimately, their commission could equally have served devotional or political aims.

However, as Carter again observes, there can be no doubt that in executing her plan the empress was acting on a devotional instruction contained in the sutra itself:

‘A small section from the narrative portion of the Sutra, which forms as it were the introduction to the charms, is enough to indicate how this printing naturally fitted into the Buddhist scheme of salvation:

A Brahmin who was sick went to visit a seer in a garden. The seer said, “You must die in seven days.” So he went to Buddha, pleading that Buddha would save him, and offering to become his disciple. Buddha said to him, “In a certain city a pagoda is fallen. You must go and repair it, then write a dharani [charm] and place it there. The reading of this charm will lengthen your life now and later bring you to Paradise.” The disciples of Buddha then asked him wherein the power of the dharanii charm lay. The Buddha said, “Whoever wishes to gain power from the dharani must write seventy-seven copies and place them in a pagoda. This pagoda must then be honored with sacrifice. But one can also make seventy-seven pagodas of clay to hold the dharani and place one in each. This will save the life of him who thus makes and honors the pagodas, and his sins will be forgiven. Such is the method of the use of dharani. … The size of the pagodas shall be from an inch to a cubit in height or yet ten feet. From these pagodas, if the heart is set at rest by contemplation, shall come forth a wonderful perfume.” The Boddhisattva said, “… I will speak of the impressing of the law of the dharani upon the heart. This dharani is spoken by the nine-hundred and ninety-nine thousand Bodhisattvas, and he who repeats it with all his heart shall have his sins forgiven. … So shall ninery-nine copies be made of each of these dharani, and they shall be placed within the pagodas. … These shall be honored with offerings and incense and flowers and there shall be a procession around them seven times while the dharani is recited. Then will great salvation be wrought.”

In the face of the discrepancy in numbers between the directions given by Buddha and by the Boddhisattva, the empress evidently tried to be on the safe side and insure long life by ordering a million copies of the charm – and by so doing, she introduced printing to the world. The immediate purpose of her project failed, for she died about the time the pagodas were distributed, but the by-product of her act became one of the world’s greatest civilizing forces. It is typical of the international character which printing has always possessed that this first printing project was in an Indian language in Chinese character and was carried out in Japan.’ (ibid., pp. 37-8).

Most of the extant pagodas have lost their printed dhāraṇī, and those that have survived are typically in a state of decay. As noted by Yiengpruksawan in 1987: ‘Their fate after the 8th century was unhappy; by the modern period most were lost, with Höryüji remaining the sole temple that still maintained a collection. When the Höryüji collection was surveyed in 1908, there were 43,930 pagodas but only 1,771 darani. Today Höryüji owns 102 pagodas and 100 darani.’ (Mimi Hall Yiengpruksawan. One Millionth of a Buddha: The “Hyakumantō Darani” in the Scheide Library. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 48, No. 3, Spring 1987, pp. 224-238)

The Empress Shōtoku remains one of the most fascinating figures in early Japanese imperial history. The daughter of Emperor Shōmu, she had previously reigned as the Empress Kōken (孝謙天皇) from 749 to 758 CE. The Empress Kōken ascended to the throne at the age of 31, and ruled under the influence of her mother, the former empress consort Kōmyō, and her nephew, Fujiwara no Nakamaro. Kōken was succeeded by the Emperor Junnin, and the retired Empress took Buddhist oaths and became a nun. In this period she formed a close personal relationship with the monk Dōkyō, with whom she is speculated to have had a romantic relationship. Despite her retirement, the former Empress retained an interest and influence in Japanese imperial politics. After a power struggle developed between Kōken and Fujiwara no Nakamaro, the tension between the opposing camps culminated with the Fujiwara no Nakamaro Rebellion (藤原仲麻呂の乱) of 764 CE. Nakamaro’s troops were defeated and Kōken re-ascended the throne as the Empress Shōtoku. The monk Dōkyō was soon thereafter appointed Grand Minister, and in 766 he was promoted to Hōō (priestly emperor), even making an attempt to ascend the throne himself in the year 769.

In the twentieth century, a printed copy of the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra, known as The Great Dharani Sutra, was discovered in Korea. It is speculated to have been printed in the early eighth century. Printing in China is believed to have had its origins even earlier, in the seventh century CE during the Tang dynasty, and there are a handful of fragmentary examples suspected to be from this date in museums in China. However, the date of none of these specimens has been verified, and there is no comparable example of a printed document from such an early date that has appeared on the market in recent times. In addressing the claims of earlier printing survival in Korea and China, Yiengpruksawan notes that ‘Both views warrant caution pending the discovery of documentation on its production compable to that which exists for the Hyakumantö darani. The Hyakumantö darani remains the most completely documented and firmly dated example of early printing.’ (ibid., p. 238)

Collectors hoping to locate other early examples of printing in Japan of such antiquity (i.e. from the 8th century CE) will be disappointed. After the commission of the Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī, mechanical printing in Japan went into decline. It remains unclear whether this was due to the cost of the endeavour, or the ritualistic implications of the printed prayers. Woodblock printing of text would not be revived until the 10th or 11th century, with woodblock books only beginning to be published more regularly in the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī are, collectively speaking, an extraordinary class of artefact dating to the earliest period of printing technology. They also provide a record of the practices and beliefs of Buddhist society in Japan in the Nara period. Most extant examples are in Japanese collections; there is a single example in Australian collections (State Library of Victoria, acquired from us in 2024).

Most, if not all, examples of the Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī found in Western collections can trace their origins to the Horyuji Temple, Nara, Japan. In 1908 a number of Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī were given to supporters who donated funds towards the maintenance of the temple. These were typically contained in an early twentieth-century box which recorded these details, although the present example is presented in a modern box. Other examples with the provenance of the Horyuji Temple, 1908, are held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum (transferred from the British Library, originally acquired in 1909), and the State Library of Victoria (Melbourne).

This example has been sourced from the collection of Mr. Masaji Yagi, owner of Azuchido Rare Books, Tokyo, former President and current President of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of Japan. Mr. Yagi writes about the Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī in his recently published autobiography 古典籍の世界を旅する : お宝発掘の目利きの力 [ = A journey through the world of classical books: the power of discerning eyes to unearth treasures] (Tōkyō : Heibonsha, 2021, pp. 208 – 209).

A great treasure and rarity in the history of the printed word, from a distinguished Japanese collection.

Provenance:

(probably) Horyuji Temple, Japan, deaccessioned 1908

unknown

Azuchido Rare Books, Tokyo

acquired from the above