# 39208

BARRY, Zachary (1827-1898)

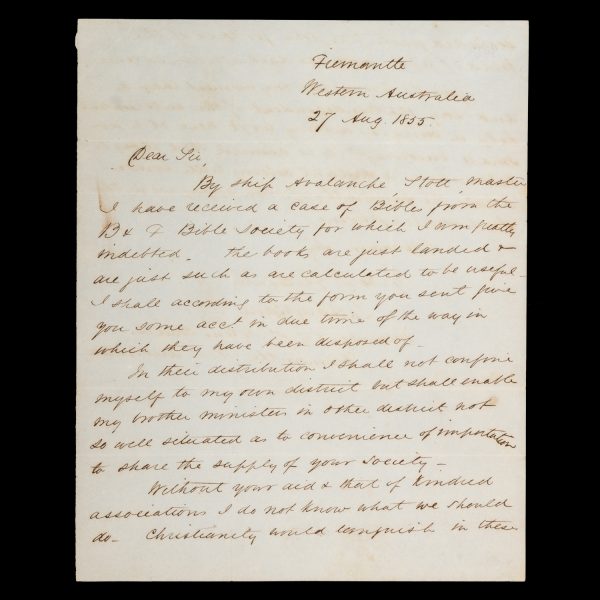

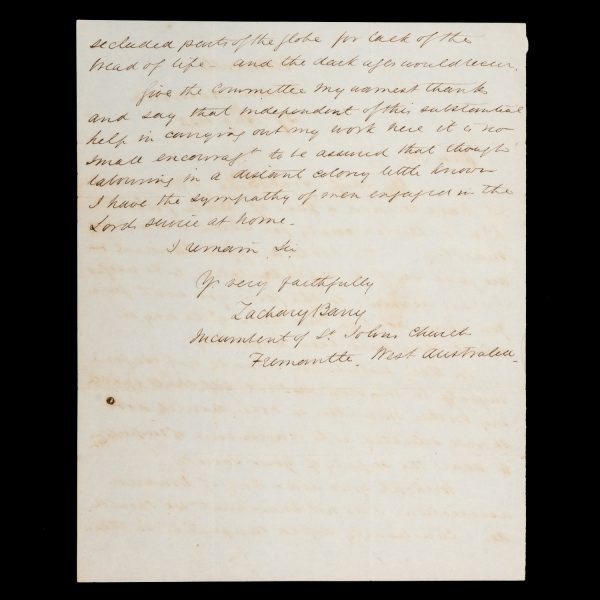

Zachary Barry, minister of St. John’s, Fremantle, Western Australia: autograph letter signed, dated 27 August 1855, re. receipt of a shipment of Bibles from the British and Foreign Bible Society.

$1,750.00 AUD

[2] pp, quarto (250 x 200 mm), manuscript in ink on unwatermarked writing paper; headed ‘Fremantle, Western Australia, 27 Aug. 1855’, the letter is addressed simply ‘Dear Sir’ and is signed at the foot ‘Yrs. very faithfully, Zachary Barry, Incumbent of St. John’s Church, Fremantle, West Australia’; Barry advises of the safe arrival from London, per ship Avalanche, of a case of Bibles sent by the British & Foreign Bible Society, ‘for which I am greatly indebted … I shall according to the form you sent give you some acct. in due time of the way in which they have ben disposed of. In their distribution I shall not confine myself to my own district but shall enable my brother ministers in other districts not so well situated as to convenience of importation to share the supply of your Society. Without your aid & that of kindred associations I do not know what we should do. Christianity would languish in these secluded parts of the globe for lack of the bread of life – and the dark ages would recur … it is no small encouragement to be assured that though labouring in a distant colony little known, I have the sympathy of men engaged in the Lord’s service at home.’; written in Barry’s neat and easily legible hand, the letter is complete and very well preserved (although without its original envelope).

An early, significant and unrecorded item of outgoing correspondence from Western Australia, shedding light on the extent to which the first clergymen and missionaries in the colony relied on such organisations as the British and Foreign Bible Society to carry out their ministry.

Zachary Barry had been appointed by Governor Fitzgerald to replace Robert Postlethwaite as Anglican minister at Fremantle in 1853. John Ramsden Wollaston, Anglican Archdeacon of Western Australia, commented in 1856 that Barry and his wife, Elizabeth, were a zealous and efficient couple who had ‘won respect and esteem from all the best portion of the community’ (Alfred Burton, Church beginnings in the West. Perth : Muhling, 1941, p. 62).

From the ADB:

‘Zachary Barry (1827-1898), Church of England clergyman, was born on 1 February 1827 near Cork, Ireland, son of David Barry, medical practitioner, and his wife Mary, née Collis. He was educated at Trinity College, Dublin (B.A., 1849; LL.D., 1868), winning the vice-chancellor’s prize and distinction in mathematics. He was made deacon in 1850 and ordained priest in 1851 by Bishop Graham of Chester on the title of the curacy of St Mary, Edge Hill. This Liverpool parish was well organized and progressive, and its incumbent, Frederic Barker, was soon to become bishop of Sydney. After two years in Liverpool, where an able company of Irish-born Evangelical clergymen gave his own strong Protestantism a sense of purpose, Barry went to Western Australia for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel as a government chaplain. In 1853 he was appointed to St John’s, Fremantle, and soon showed his vigour as a parish minister and as an exponent of his school of churchmanship. But his deafness became a problem and in 1861 he returned to Ireland. He was acting as organizing secretary for Irish Church Home Missions when Bishop Barker, on a visit to Britain and himself a former Irish missioner, induced him to return to Australia.

Barry went to Sydney in 1865 and was placed at Randwick, near the episcopal residence. Three years later he went to Paddington, where he completed the fine stone church of St Matthias, built a parsonage and school, served as chaplain to the Victoria Barracks and maintained a popular and efficient ministry until 1893.

The diocese contained many Irish clergymen of Evangelical sympathies and wide learning, but Barry soon made it clear that he was not content with an orthodox parochial role. Mild and scholarly in private, he was an ardent controversialist and an effective public speaker, a militant Protestant and an Orange sympathizer. In an exchange of letters, Do Catholic Bishops Swear to Persecute Protestants? (1867), he took the field against a Roman Catholic apologist, and in An Erring Sister’s Shame (1867) he attacked both Catholics and High Church Anglicans. The attempted assassination of the Duke of Edinburgh in 1868 provoked The Danger Controlled, an accusation of a Catholic-Fenian connexion. Finally he joined a Presbyterian clergyman, John McGibbon, to found and edit the Protestant Standard, a journal which waged relentless war on Rome.

Barry’s enthusiasm and energy soon took a more positive course. He had never endorsed the compromise of the Public Schools Act (1866) and in 1874 he helped to found the Public Schools League. Barry believed that a uniform National system, eventually to be free and, with due allowance for private schools, compulsory was the only possible educational policy. The system should be ‘secular’ in the sense of being undenominational, but he wanted to retain and extend the practice of special religious instruction by the clergy and the use of the Irish National religious syllabus. He denied the charge that the league was godless and he fought against the rival Bible Combination’s objective of the study of the scriptures in open class. Barry was as active as the Baptist minister, James Greenwood, in promoting the cause of the league but, unlike Greenwood, who left the pulpit and entered parliament, he declined political offers and remained essentially a churchman. His opposition to Roman Catholicism was an important part of his educational purpose.

Officially the Church of England stood for the denominational system and it became Barry’s objective to persuade the Diocesan Synod to change this policy. In 1875-78 he campaigned hard in synod and gained the support of influential laymen and some clergy. But Barker, while agreeing that religious instruction and educational methods needed improvement, remained firm. Relations between Barry and his bishop became strained; a less forbearing prelate would have taken action against the public attacks made on him. As a result Barry was able to weaken but not to alter the educational position of the Church. While Bishop Barker regarded him as a disruptive force he could not take what he thought to be his rightful place as a leader of the dominant Evangelical party.

In 1878 Barry’s voice failed (the diagnosis was ‘clergyman’s throat’) and he had to take leave. He went overseas and gained some physical relief but his absence weakened his influence and he played a smaller part in the events of the 1880 Act. This legislation did not meet his entire programme but it provided him with the new role of persuading a still reluctant Church to co-operate in the working of the Act. Meanwhile Barry extended his interests. He supported the Christian Defence Association and published in 1884 a pamphlet Christian Dogma Unaffected by the Common Hostile Criticism. He brought his scholarship into full play to combat ‘German neology’ and ‘popular materialism’, ideas with which he had already come to grips in public debates at the Victoria Theatre in the mid-1870s. Barry championed moral reform; he also fought hard against the Anglo-Catholic influences which were becoming important in the Church. On these separate counts he was able to acquire a degree of authority that he had hitherto lacked among Evangelical Anglicans.

Barry retired from parish work in 1893 and gave up his editorial work in 1895. Increasing deafness was already hampering his public activities and he lived a quieter life at the Glebe until his death, after a short illness, on 4 October 1898. Barry was buried in the cemetery of his first Sydney church, St Jude’s, Randwick. He was survived by his wife Elizabeth, née Robertson, who had borne him six sons and four daughters and died on 21 December 1902.’